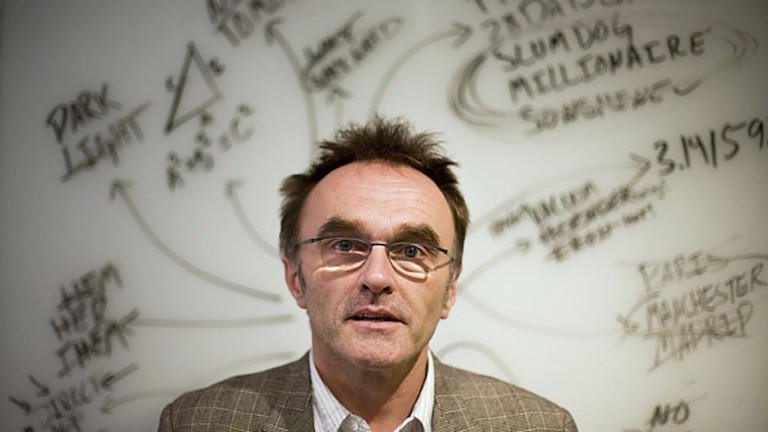

Interview :: Danny Boyle

April 11th 2013

FBi Radio

Trance is the new highly anticipated hypno-thriller from Scottish director Danny Boyle, known for his very eclectic taste in filmmaking.

He’s been behind acclaimed titles such as the Oscar winning Slumdog Millionaire, 127 Hours, 28 Days Later, Shallow Grave and most famously, Trainspotting. Trance is the first film Boyle’s made since directing the London Olympics Ceremony of last year which was described as a “national antidepressant.” Thankfully, Trance is anything but. It’s an urgent, violent thriller with more twists than a pretzel.

Kate Jinx, host of FBi’s Picture Show, spoke to the very energetic and eloquent Danny Boyle over the phone from London to discuss film noir, surrealism and bringing back old characters.

————————-

KJ: Trance crosses a lot of genres, it’s a thriller with film noir elements. Were you very aware of the tropes of noir? What you wanted to work with and what you wanted to change?

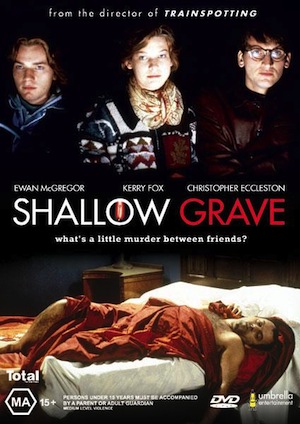

Danny Boyle: Yes, I worked again with the guy who wrote the early films Shallow Grave and Trainspotting, John Hodge, and this is a three-hander like Shallow Grave and it’s again concerned with characters where you don’t know who to trust and we deliberately played with that with James McAvoy at the beginning of the film. We were also aware of the three-hander in crime, like with Shallow Grave, it’s very noirish and having it set in a city that could be any city where crime and anonymity can flourish. The film begins like an art heist movie but it’s not about a stolen painting, it’s about stolen memories of course. You do become aware that you’re using genre to try and pull you into the mainstream. We’re making quite difficult films but for a mainstream audience and you’re trying to use the genre and vehicle to get you in there.

KJ: So you’re using what you have and then flipping it.

DB: Yes. It’s clearly like noir, clearly [Elizabeth is] a femme fatale. She has classic femme fatale behaviour. She’s manipulating men, she’s using her allure, her appeal, her sensuality, she’s manipulating [the men] against each other and towards her own goal but by the end of the movie… she’s not the icy blonde from the classic cold noir. Instead it has a story in it that has heat and damage and emotion as well, and a kind of relevance she holds.

KJ: She’s so interesting, that character, she has the femme fatale cliches – she’s seductive, she’s witty, but she has more agency than usual.

DB: It’s the reason we did the film really. There’s lots of reasons to do the film – it’s a delicious story, it’s a delicious opportunity for a filmmaker to occupy a genre and yet not. The real reason is that I had never made a film with a woman absolutely in the engine room.

KJ: What about Kerry Fox’s character in Shallow Grave?

KJ: What about Kerry Fox’s character in Shallow Grave?

DB: But they remain a threesome, and the movie twists and turns and then eventually it’s Ewan McGregor really at the end, I guess. But with this film…clearly by the end it is [Elizabeth’s] movie, in a way, and she refused to live her life on anyone else’s terms. And I know why it is – it’s funny to admit but it’s true – all the films we’ve done are all about essentially one idea – that you take a character and place them against insurmountable odds and they overcome them. It’s a classic quest idea of filmmaking and if you look at the story in chronological order – which clearly the audience don’t – but if you did, she is the person who faces the insurmountable odds and has to overcome them. And lives her life in her own way and against the threat of violence which initially is embodying one person but eventually there are five men… but she does not run away. She refuses to run away. She uses her own skill set to live her life her own way. And I love that. And it allows you to make a film that is full of the visceral appeal of the films we usually make and yet it’s surprisingly about someone different.

KJ: It’s interesting that you bring up that this theme has been running through all your films because your work is incredibly varied – zombies, junkies, newly one-armed adventurers! Are you just drawn to what you’re drawn to and you see this later?

DB: Yes, consciously or organically you’re drawn to that storyline and you obviously empathise with that as you make the film because that’s what appeals to you (laughs). It’s funny actually, because it is subconscious and then you think about the films, they are pretty much like that. You think about the guy in Slumdog [Millionaire], even that film – Dev Patel – it’s impossible the odds he’s up against and obviously the guy with one arm – he’s obviously, CLEARLY got problems (laughs), and somehow he triumphs. It gives you that surge – which I do like – to go out of a film feeling that charge that you have been lifted back into life after coming to the cinema. You’ve been lifted back into life no matter how dark story elements have been. But yeah, one of the problems of doing press – which I do believe in, I think it’s an important part of the process – but you become quite self conscious about what you’re doing. Thankfully you tend to forget that self consciousness when you go back to your day job, you know just beginning to work on scripts for your next film or theatre or whatever it is you’re going to work on next.

KJ: You’ve been very hands on with the collateral sounding the film, particularly the narrated website that you did. Is that a changing role for filmmakers that you see or were you just particularly keen to be involved with this film in particular?

DB: I think it is a changing role, it’s definitely evolving. If you compare the way you promoted your early films to now and the access people expect to have as part of their new communication world, you know, clearly, people have to be able to speak to you directly. It’s an inevitable part of it. I mean, obviously some directors take the more mysterious route and actually be less available to that process but I learn quite a lot about filmmaking from talking about it actually. You do learn about what you’ve done and you should have done, all that kind of stuff so I like the process. So as it develops – the modern world of communication – they offer you another opportunity or ask you to participate like that. I’m happy to do so for as long as people can tolerate it.

KJ: You’re processing your work by talking about it afterwards. It’s probably saving you a load in therapy.

DB: (laughs) You are processing it yeah. It’s very true. You don’t realise it…. you begin the process rather inarticulately to be honest and you learn. When you’re talking to journalists you learn what you’re talking about. It’s a funny process actually because people say ‘oh how can you bare to do this? Saying the same things over and over?’ and obviously there’s a degree of repetition but I think you’re growing as you do it, you’re learning more as you go on. I quite enjoy the process. I don’t resist it… the kinds of films we make… you have to work hard to get people to come and see them because they don’t necessarily have the ingredients of big movies. They don’t have the automatic appeal of a classic genre film with a big star in it… you’re saying ‘come watch this instead’ because the ingredients are slightly more challenging. You’re saying these are not the absolute megastars of Hollywood but they are fucking good actors and actually they’re better actors. These are proper, proper actors and I’ll do anything to draw people in to come and see them.

KJ: You also stepped majorly outside of the usual film realm directing the London Olympics Opening Ceremony, which one British magazine described as a “national antidepressant.” It must have been so wonderful to shift gears after that and make something so violent and so urgent with Trance.

DB: Yes, you’re absolutely right . Although [the opening ceremony] was great fun and it turned out alright. But actually the process of making it was pretty soul destroying sometimes because it was very slow. And you were literally working on it for two years and you’re doing one performance only… it’s essentially and has to be overwhelmingly positive, a national celebration, family friendly, all that kind of stuff so it’s lovely to be on the dark side at the same time. To be making something which we called the evil mad relative. And I’m very lucky to be able to do that. But you have to warn people as well that it’s not featuring Mary Poppins.

KJ: (laughs) It’s not all about violence and mind bending though, I left completely fascinated by Goya’s Witches In The Air (pictured left). Not a painting I was familiar with. Was that in the original script or was that an addition of yours?

KJ: (laughs) It’s not all about violence and mind bending though, I left completely fascinated by Goya’s Witches In The Air (pictured left). Not a painting I was familiar with. Was that in the original script or was that an addition of yours?

DB: No, the script left it open, and we immediately jumped at Goya… he is the first modernist really. The first great painter of the mind. He went inside the dreams and nightmares of the mind and that’s perfect given what you’ve got to do with McAvoy’s mind. It’s perfect, it’s great for that. And also the picture is all symbolic of Simon’s struggle. That figure that’s cloaked, that doesn’t have full vision of what’s going on around you, and what’s going on above is surreal, a kind of sacrifice with male witches, it’s perfect… If you’re eventually going to move to a surreal image like Vincent Cassel’s head cut in half, you need to earlier on in the film introduce the idea of the surreal and that is the Goya. There’s a surreal element to what he was doing and of course he was the guy who first depicted the female form as it was rather than an idealised version of it. There were a lot of reasons why he was perfect [for the film] and he’s a genius painter as well.

KJ: Well I’d be remiss not to mention all the talk of a Trainspotting follow-up. What is it about those characters that you’d like to bring back? Sure, I miss Spud, but what is it about them, that you want to bring out again?

DB: I find it astonishing – and this is true of me of as well – how people remember the character’s names. I have never made a film where I can remember what all of the characters names were! But people remember Spud…

KJ: and Diane and Sickboy…

DB: I know! It’s weird! (laughs) I mean obviously the actors were fantastic in it… and there’s always been pressure with a success like that, always been pressure to do a sequel. We considered it ten years ago at the tenth anniversary but the actors weren’t old enough, they didn’t look different enough. We always thought if we went back to it, we’d go back to it in the way that those documentaries do…

KJ: The 7 Up series?

DB: Yes, 7 Up, 14 Up, 21 Up. And there’s something riveting about looking at ourselves in the passage of time, which you do through the characters. Because you do, you think, ‘that’s my mate from school, she was like that and I wonder what happened to him’. You’ve got this town that they live in – have they stayed in the place? Are they still bound together? Or the fracture of their friendship – is that complete? What brings them back together and obviously they will come back together if you’re going to make that kind of film. So it’s got a lot of potential and integrity I think. I don’t think anyone of us would make a film that just cashed in on the original because it was obviously made with a lot of passion and it was a very extreme film and yet it took off… and it’s a great one for double programming! (laughs)

————————–

Picture Show with Kate Jinx is on every Saturday morning at 10am on FBi.